Overt Evidence for the Efficacy and Safety of Thalidomide in Gastrointestinal Bleeding from Small Intestinal Angiodysplasia

Philip N. Okafor, MD, MPH

Philip N. Okafor, MD, MPH

Senior Associate Consultant, Department of Gastroenterology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida

This summary reviews Chen H, Wu S, Tang M et al. Thalidomide for Recurrent Bleeding Due to Small Intestinal Angiodysplasia. N Engl J Med 2023; 389(18):1649-1659.

Access the article through PubMed

Correspondence to Philip N. Okafor, MD, MPH, Associate Editor. Email: EBGI@gi.org

STRUCTURED ABSTRACT

Question: Does a 4-month treatment course of oral thalidomide (50 mg or 100 mg daily) reduce the number of bleeding episodes in patients with recurrent bleeding from small intestinal angiodysplasia?

Design: Randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, conducted between April 2016 and December 2020.

Setting: Ten hospitals in China.

Participants: Adults with at least 4 episodes of recurrent bleeding in the previous year from small intestinal angiodysplasia (SIA) were enrolled. The existence of SIA had to be confirmed via capsule endoscopy, balloon-assisted enteroscopy, or both.

Intervention/Exposure: Fifty mg or 100 mg oral thalidomide vs placebo for 4 months with 1:1:1 randomization.

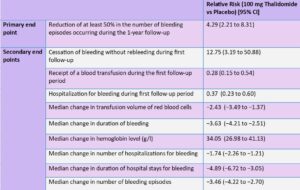

Outcomes: The primary endpoint was a reduction of at least 50% in the number of bleeding episodes occurring during a 1-year follow-up period compared with the number of bleeding episodes in the 1-year observation period before 4-months of treatment with thalidomide. Secondary endpoints included cessation of bleeding during 1-year follow-up period; blood transfusion during 1-year follow-up period; hospitalization for bleeding during 1-year follow-up period. Changes during the 1-year follow-up period compared to the initial 1-year observation period were calculated for transfusion volume of red cells, duration of bleeding in days, hemoglobin level, number of hospitalizations for bleeding, duration of hospital stay (in days) for bleeding, and number of bleeding episodes.

Data Analysis: Intention-to-treat analysis and a Fisher exact test were used to compare the primary endpoint across all 3 groups. There was no adjustment for multiple comparisons. The sample size was calculated for comparison of 100 mg thalidomide group and 50 mg thalidomide group vs placebo, but not intended to determine if 100 mg thalidomide was superior to 50 mg thalidomide.

Funding: The National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, Gaofeng Clinical Medicine.

Results: The median age of participants was 62.2 years (range 26-69.6 years), 59.3% (n=89) were women, and all 3 groups were comparable in demographics and clinical characteristics. The primary endpoint, a reduction of at least 50% in the number of bleeding episodes occurring during a 1-year follow-up period compared with the number of bleeding episodes in the 1-year observation period before 4-months of treatment, was significantly better for thalidomide 100 mg and thalidomide 50 mg treatment groups vs placebo: 68.6% and 51% vs 16%, respectively, P<0.001. The incidence of rebleeding was also significantly lower with 100 mg thalidomide and 50 mg thalidomide vs placebo: 27.5% and 42.9% vs 90%, respectively.

Among other secondary outcomes, hospitalization due to recurrent bleeding was also significantly lower with 100 mg thalidomide and 50 mg thalidomide vs placebo: 27% and 35% vs 74%, respectively, as well as need for blood transfusion: 18% and 25% vs 62%, respectively. Other secondary outcomes followed the same trend (Table 1).

Although only 3 patients stopped treatment due to side effects (1 for abnormal liver function and 2 due to dizziness), adverse events were common with thalidomide, including constipation (22%-26%), limb numbness (14%) and dizziness (10%-20%).

COMMENTARY

Why Is This Important?

The increasing use of antiplatelet agents and novel anticoagulants has been met with an uptick in hospitalizations_for_gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.1 In particular, small bowel bleeding presents a treatment challenge for clinicians with rebleeding rates as high as 45%.2 With the advancement in endoscopy technology, balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE) has become an important option for treating small-intestinal angiodysplasias, but it isn’t available in many hospitals. Even when available, BAE can be challenging to perform, may not identify a bleeding source, is associated with complications including bowel perforations, and may not be suitable for medically unstable patients.3 Therefore, it’s also crucial to explore pharmacological therapies, too, especially because SIA are believed to recur over time. An effective pharmacological option for SIA has the potential to be a game changer by reducing hospitalizations, transfusion requirements, and endoscopy utilization.

Somatostatin analogs, such as octreotide 40 mg IM, every 28 days, decrease blood flow to splanchnic vasculature in the GI tract and may decrease transfusion requirements in these patients. However, most of the evidence supporting its use comes from small observational studies,4 and it does not have any disease-modifying effects on eradicating or preventing SIAs.

SIAs are essentially collections of dilated arterial and/or venous capillaries. Thalidomide decreases expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, which are at high levels in patients with angiodysplastic lesions.4-5 Thus, it’s considered antiangiogenic and may be a disease-modifying agent whose benefit persists even after medication is stopped. However, there has been a paucity of evidence on therapeutic efficacy,4 appropriate dose and duration of use, and significant concerns about dose-dependent side effects. In this landmark study, Chen et al conducted the first well-designed, large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of thalidomide for the treatment of bleeding from small intestinal angiodysplasia.

Hospitalization due to recurrent bleeding was significantly lower with 100 mg thalidomide and 50 mg thalidomide vs placebo: 27% and 35% vs 74%, respectively, as well as need for blood transfusion: 18% and 25% vs 62%, respectively. Adverse events were common with thalidomide, including constipation (22%-26%), limb numbness (14%) and dizziness (10%-20%).

Caution

The authors highlight some limitations of this clinical trial. They emphasize that a positive fecal occult blood (used to identify GI bleeding) in patients who are not hospitalized or who do not receive any intervention may not be clinically meaningful. They also did not compare the 2 doses of Thalidomide (100 mg and 50 mg) against each other. Importantly, they excluded patients with aortic stenosis and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, 2 SIA risk factors. They also excluded patients on anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy, who account for a significant proportion of patients hospitalized for small bowel bleeding. In addition, their study population was not as diverse as the US population which may limit the generalizability of the results. Finally, among the “responders” without rebleeding in the follow-up period, 20 out of 42 re-bled in the subsequent 3 months-27 months, suggesting a loss of effect and potential need for re-treatment with thalidomide.

My Practice

In my clinical practice, I have rarely used thalidomide for small bowel bleeding attributable to SIA, partly because I have easy access to BAE at my center. Also, thalidomide is still regarded as a chemotherapeutic agent at some hospitals and prescription privileges are reserved for oncologists. In the rare clinical situations I have had to recommend thalidomide for GI bleeding, I have referred those patients to the hematology-oncology clinic, where it is prescribed and monitored for side effects. For these reasons, I have preferentially used long-acting somatostatin analogs when a pharmacological option is indicated for SIA bleeding. This can be administered monthly, increasing medication adherence.

For Future Research

This excellent study provides level I evidence on the efficacy and safety of 2 different thalidomide doses in reducing the risk of bleeding in patients with known small intestinal angiodysplasia. Future studies powered to compare both doses (and even lower doses), identify the ideal duration of treatment, and role of re-treatment are needed. In addition, more data are needed on patients with a higher cardiovascular disease burden who tend to be disproportionately affected with small intestinal angiectasia. Comparative trials between thalidomide, somatostatin and other antiangiogenic agents would also be helpful.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Okafor reports no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Holster, I.L., et al., New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2013; 145(1): 105-112 e15.

- Gerson, L.B., et al., ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110(9): 1265-87.

- Levy, I. and I.M. Gralnek, Complications of diagnostic colonoscopy, upper endoscopy, and enteroscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 30(5): 705-718.

- McFarlane, M., et al., Emerging role of thalidomide in the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding. Frontline Gastroenterol 2018; 9(2): 98-104.

- Chen, H.M., et al., [The mechanisms of thalidomide in treatment of angiodysplasia due to hypoxia]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2009; 48(4): 295-8.