Family Matters: Increased Risk of Colorectal Cancer among Individuals with Family History of Polyps

Ravy K. Vajravelu, MD, MSCE1 and Robert E. Schoen, MD, MPH2

1Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and Staff Gastroenterologist, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

2Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology, Chief, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

This article reviews Song M, Emilsson L, Roelstraete, Ludvigsson J. Risk of colorectal cancer in first degree relatives of patients with colorectal polyps: Nationwide case-control study in Sweden. BMJ 2021; 373: n877.

Correspondence to Ravy K. Vajravelu, MD, MSCE, Associate Editor. Email: EBGI@gi.org

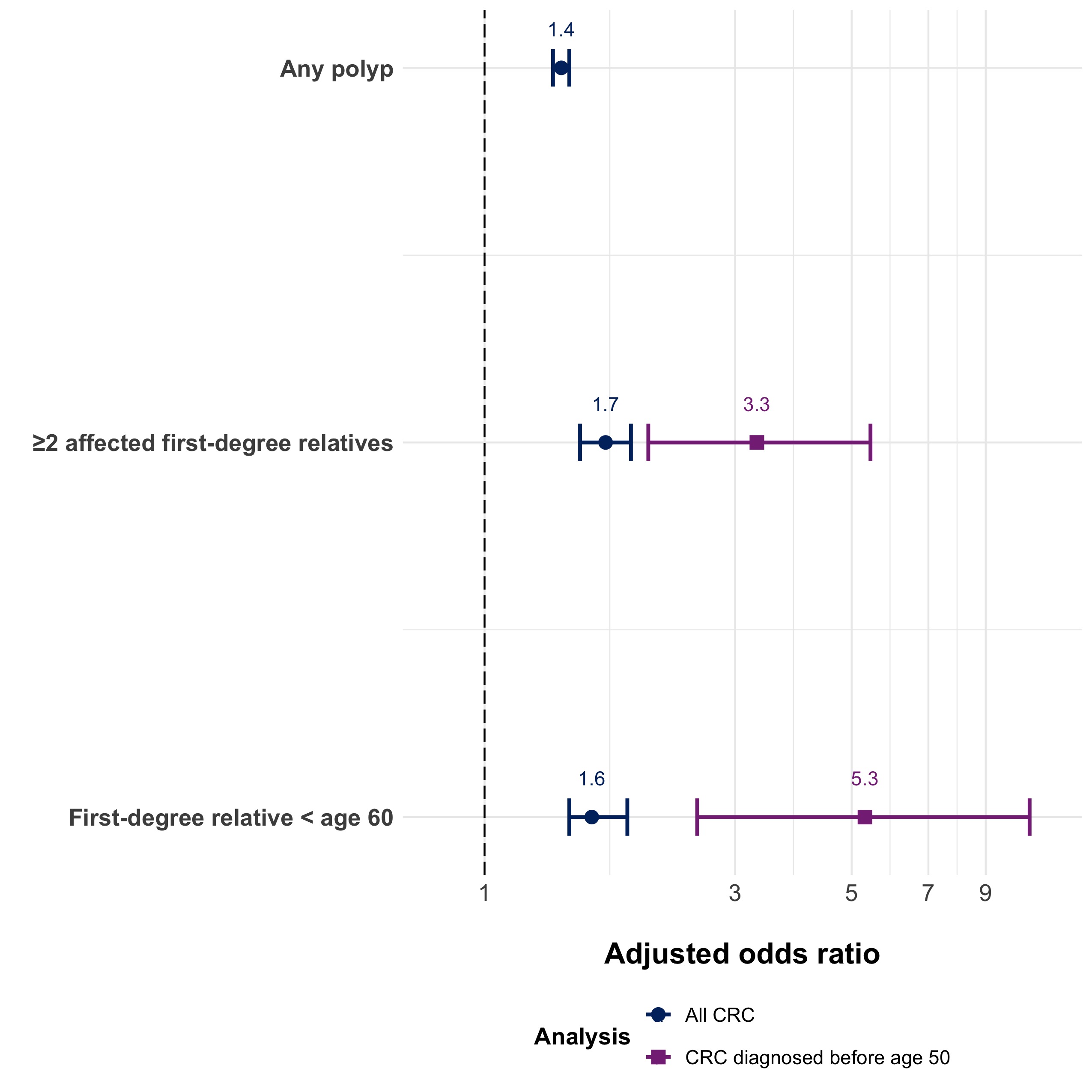

CRC. In this study, the OR is approximately equivalent to risk of developing CRC. The authors also performed a subgroup analysis of cases with CRC before age 50 and several secondary analyses assessing the effect of the number of family members with polyps/CRC and the age of family members at the time of polyp/CRC diagnosis.

Figure. Adjusted odds ratio of developing CRC based on family history of polyps that preceded the diagnosis of CRC.

Figure. Adjusted odds ratio of developing CRC based on family history of polyps that preceded the diagnosis of CRC.

Notes: Adapted from M Song et al. BMJ 2021. ORs are adjusted for sociodemographic factors, medical comorbidities, and family history of CRC.

___________________________________________________________________________________

COMMENTARY

Why Is This Important?

Although US gastroenterology societies have recommended earlier CRC screening for individuals with a family history of CRC or advanced polyps since the inaugural guidelines in 19971-3, these recommendations have not been universally emphasized. For example, recent guidelines from the American Cancer Society and US Preventative Services Task Force focus only on average-risk screening, and guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology primarily address genetically-determined cancer syndromes such as Lynch Syndrome and Familial Adenomatous Polyposis4-6. Differences in society recommendations are likely related to a lack of high-quality evidence regarding family history of polyps. For example, recommendations from the US Multi-society Task Force on CRC are extrapolated from studies assessing the risk of CRC amongst those with a family history of CRC.7,8 Prior observational studies assessing the risk of CRC based on family history of polyps are limited by methodologic biases.9,10 For example, a diagnosis of CRC that triggers a colonoscopy in first degree relatives which then identifies adenomas is not equivalent to finding a colorectal adenoma, which is then used to identify a family member at increased risk for CRC. The former is an association; the latter is more suggestive of a causal link because of temporality. This study overcomes this bias by restricting the analysis to polyps in first-degree relatives identified before the diagnosis of CRC. Moreover, these observational data from the Swedish national health registries are among the best available. They are uniquely suited to assess the association between family history of polyps and CRC because of their decades-long follow-up, histopathological confirmation of CRCs, and access to accurate family linkage. The authors also performed several subgroup and sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the results to changes in the statistical methodology. These analyses consistently demonstrated increased risk of CRC among those with a family history of polyps.

Key Study Findings

The main study find was that having a first-degree relative with any type of colorectal polyp increases personal risk of CRC by 40%. The risk was higher if there were more first-degree relatives with polyps or if the first degree relatives were diagnosed with polyps at younger ages (Figure).

Caution

Although this is an exceptionally well-designed research study, there are methodological limitations which may impact interpretation of the results. First, the authors sought to isolate the contribution of family history of polyps from the contribution of family history of CRC through statistical adjustment. Because polyps are precursors to CRC11, it is unlikely that the effect of family history of CRC could be completely removed from the effect of family history of polyps through statistical methods alone. Therefore, the reported ORs may not accurately reflect the association between family history of polyps and CRC. Second, the definition of advanced polyps in this study is different from the definition used by the US Multi-society Task Force on CRC. This is in part due to lack of data on number of polyps, size of polyps, and difficulty distinguishing sessile serrated polyps from hyperplastic polyps. Inaccuracies in characterizing polyp histology means physicians should take caution when interpreting the reported ORs. Third, the case-control design of this study makes it susceptible

to bias. In particular, since there is not universal CRC screening in Sweden, individuals with family history of polyps may seek CRC screening more often than individuals without a family history of polyps. This could artificially increase the OR of the association of family history of polyps with CRC through ascertainment bias. However, the long duration of follow-up mitigates this potential bias.

Our Practice

Guidelines regarding screening in association with a family history of polyps are inconsistently applied in practice, and we continue to lack definitive, prospective data on the yield of screening. Despite the limitations of this study, it addresses a major gap in the literature, particularly by confining the assessment of polyps to those diagnosed before the identification of CRC in the family. Furthermore, the results are consistent with guidelines from the US Multi-Society Task Force on CRC, which we apply in our own practice. Specifically, these guidelines recommend CRC screening at the earlier of age 40 or 10 years before the family member’s first diagnosis of advanced adenomas (any polyp greater than 1 centimeter, 3 or more adenomatous polyps in a single colonoscopy, villous histology, tubulovillous histology, traditional serrated adenomas, or high-grade dysplasia). If a patient has a first-degree relative with non-advanced adenomas, then the guidelines recommend CRC screening equivalent to that of average-risk patients: Initiate at age 45 – 50 with repeat screening based on the results of the initial exam. Unfortunately, even when patients know that their family members had polyps, it is often unclear if the polyps were high-risk, non-advanced adenomas, or simply diminutive hyperplastic polyps. Therefore, in our communications to referring physicians, we provide documentation of the details of the findings at colonoscopy, and, in particular, whether or not advanced adenomas were discovered. We also recommend that patients with advanced adenomas encourage their first-degree relatives to discuss CRC screening with their providers.

For Future Research

The ideal study to assess whether individuals with a family history of colorectal polyps are at higher risk for CRC would be a prospective study in a country with universal CRC screening that is highly utilized. It is unlikely that this study would ever be conducted because it would require follow-up and a very large sample size. However, as the Swedish national health registries and other registries around the world improve with more nuanced polyp data, it may be feasible to address some of the limitations of this study—particularly those related to the definition of advanced polyps.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Vajravelu has no disclosures to report. Dr. Schoen reports grant support from Exact Sciences, Freenome, and Immunovia.

REFERENCES

1. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:1016-1030.

2. Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology 1997;112:594-642.

3. Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology 2003;124:544-60.

4. Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:250-281.

5. Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2021;325:1965-1977.

6. Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut 2010;59:666-89.

7. Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, et al. A prospective study of family history and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1669-74.

8. Schoen RE, Razzak A, Yu KJ, et al. Incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1438-1445 e1.

9. Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF. Risk for colorectal cancer in persons with a family history of adenomatous polyps: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:703-9.

10. Samadder NJ, Curtin K, Tuohy TM, et al. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia among family members of patients with colorectal cancer: a population-based study in Utah. Gastroenterology 2014;147:814-821 e5; quiz e15-6.

11. Jones S, Chen WD, Parmigiani G, et al. Comparative lesion sequencing provides insights into tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:4283-8.